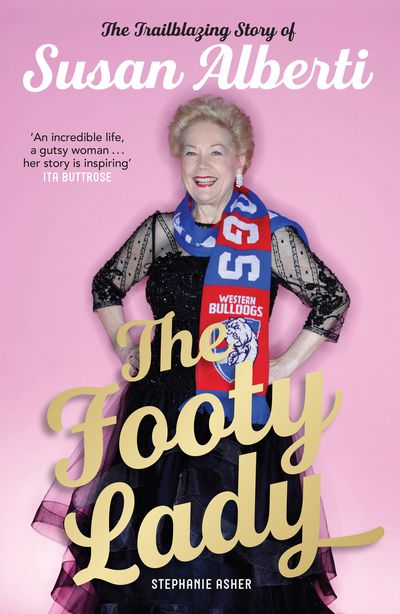

←Back to The Footy Lady

An extract from “The Footy Lady”

Chapter 11: Speaking out – Changing the Diabetes Story

Judi Moylan, who was a Western Australian member of the Australian House of Representatives from 1993 to 2013, recalls first meeting Sue in 2002, back when Sue was the national president of the JDRFA. At the time, Judi was the chair of the Parliamentary Diabetes Support Group (PDGN), which she’d established two years earlier. Sue wanted Judi’s help in setting up a local version of the Kids in the House program that had been so successful in the American Congress, enabling kids with type 1 diabetes to travel to the centre of political power and directly ask politicians for their help. Judi fully supported the idea and made an arrangement with Qantas to fly 100 children and their parents into Canberra. Following that initial project, the two women stayed in touch through their mutual interest in diabetes.

More recently, towards the end of 2015, Judi was in the middle of event preparations for the Global Forum of Parliamentary Champions for Diabetes in Vancouver when her personal assistant suddenly fell ill, which meant that Judi had to organise the event on her own. ‘By then, we had a network of 170 members of parliament across forty- one countries, and 200 invitations had just been sent out’, she says, adding that half the invitees soon confirmed their attendance, including some high-profile MPs, opposition leaders and ministers of state.

‘I rang Susan in a bit of a flap and said, “I need a dinner speaker and I thought you’d be marvellous”’, says Judi. ‘Susan didn’t hesitate. She accepted immediately and said she’d do anything I needed. She met all her own expenses. We were operating on a shoestring—she paid for her own flights and accommodation.’

Judi still remembers the emotional impact of Sue’s words at the forum: ‘There were MPs from all over the globe, not exactly the sort of people that burst into tears easily. Susan’s speech was an absolute knockout. It so deeply touched people that there was not a dry eye at the dinner’. Judi believes the power that Sue brought to her speech was her very personal story: ‘It was a very moving occasion. Susan’s story and her capacity to express the issues at stake was very, very powerful indeed. Even talking about it now sends little shivers up the back of my neck. It was the most talked-about speech for the whole of the meeting—not just the parliamentary meeting but the whole of the international event’.

Sue’s willingness to put her own story forward and show her vulnerability is one of her greatest strengths, and the key to unlocking much-needed political support. Danielle was right to encourage her mother to engage in public speaking—delivering speeches and formal presentations is a powerful leadership tool, one that Sue has honed and continues to use to the great advantage of her causes. Many prominent gures rely on speechwriters for such occasions, but Sue prefers to write her own material. Nor will she be told what to say by event organisers. She also guards her speeches closely, refusing to share notes or drafts, even with those close to her.

George Pappas first heard Sue speak at a Bulldogs president’s lunch event, before she had been appointed to the club’s board. He describes his reactions to Sue’s talk: ‘Firstly, what an incredible organisation the Western Bulldogs is to have a speech on the subject of juvenile diabetes and the work that is required to find a cure ... It was one of those things that convinced me that getting involved with the Bulldogs was a good thing. It re ected so well on the character of the club. Another reaction was, “Who is this incredible woman?”’

George explains why the speech had such a strong impact: ‘It was the way she spoke about the issue. She spoke from the heart. She was so well informed and, despite this calm and assured demeanour, there’s an underlying passion that you could sense. Sue’s not demonstrably passionate, in the sense of jumping up and down, but when she speaks about diabetes you can sense this commitment. It came through her tone of voice’.

Former Australian prime minister Tony Abbott was equally touched by Sue’s ability to articulate the issues around the disease, including the need to support medical research and generate pathos. He often heard her speak in his various political roles, including as health minister, when he first met her, then later as the nation’s leader: ‘It is such a moving story, and no parent can listen to that story without getting a bit teary. And then you instantly think, “What if one of my kids had type 1 diabetes? What would I want done?” The short answer is, “Everything that is reasonably possible”’.

As the first Australian invited onto the board of the JDRFI, Sue felt privileged and empowered to make a difference—from 1995 until 2004, she served as an international director, alongside Mary Tyler Moore and Mary’s husband Robert. Overall, through her involvement with the JDRFA, which began in 1983, Sue contributed many millions of dollars of her own money, as well as raising tens of millions of dollars from other sources. But in 2013, she decided to depart the organisation. Her formal statement announcing the end of her association with the JDRFA simply read, ‘It has become apparent that the organisation I joined thirty years ago and have championed ever since is heading in a direction that I cannot support’.

In acknowledging Sue’s contribution, the then chairman of the Australian arm of the body, Stephen Higgs, said, ‘Dr Alberti has played an important role in helping build JDRF into one of the most respected not-for-profits in Australia. We now operate in every Australian state and have supported over $100 million of research in Australia since inception, with significant growth in fundraising in recent years. We have also received a $35 million commitment from the incoming Coalition government to the extension of our Clinical Research Network’.

Sue prefers not to dwell on the matter, although her spartan comments on it indicate a lingering hurt. She does say that a change of management created a different culture, and Sue felt the focus shift away from where her passions lay—targeted funding for specific research.

Ita Buttrose says she has had similar experiences in her history with charitable organisations, but she is philosophical about this: ‘Sometimes when you’re involved in organisations and there’s a change at the top in where it’s going, you have to leave. You only can be honest and give your point of view. If you’re an honourable person and you’re not happy, if you don’t believe in where a charity is heading, then the only thing you can do is leave. It’s wrong to stay on if its course of direction doesn’t sit comfortably with you’. Ita then says of her friend: ‘Sue is not one to compromise. She goes for it all. She has her values and principles and I don’t think she’d ever desert them. If Sue was your best friend, she’d be the best best friend you’d ever have’.

It is the case that understanding where money goes is important to Sue, whose practical, businesslike approach is naturally geared towards return on investment. This is a crucial element of communicating the benefits of medical research and the need for nancial contributions. Ita shares this view, and sketches the scenario to be avoided: ‘Sometimes a concern in the community is that the donations are spent on administration instead of the cause, especially the research. Charities have an obligation to make sure every penny received is well used, and that most of the money goes towards whatever it is their stated public goals are and not to other purposes’.

After Sue’s public split from the JDRFA, the research foundation she’d set up back when Danielle was first diagnosed—SAMRF—focused on funding research into a breakthrough medical procedure known as islet cell transplantation, which in the early 2000s was the scientific focus of Tom Kay at the St Vincent’s Institute. Islets are clusters of cells in the pancreas that include the insulin-producing beta-cells. In simple terms, it is thought that transplanting these cells into a patient with type 1 diabetes could allow that person to live a relatively normal life— ‘normal’ in this context is defined as free of the need to inject insulin.

Sue’s friend Carrie Keller recalls sitting with Sue at the function where the St Vincent’s Institute made a public announcement about islet cell transplants in 2004. She says that Sue told her, ‘Had my daughter been alive, this could have saved her. All my money didn’t make a difference, I didn’t have this opportunity. But I can give this gift to another person’.

Elaine Robinson, then in her fifties, was one of a lucky handful of recipients of the treatment when it was first trialled in 2007. ‘I was lucky because my blood type was the first available match’, she explains. Today, the healthy-looking Elaine is all smiles when she talks about Sue Alberti: ‘I would go out of my way to help Sue with anything. She is such a strong, powerful woman. A very caring person’.

Elaine was diagnosed with diabetes at twenty-nine years of age. At the time she was pregnant with her son, who was born eleven weeks premature. ‘When they put me on a drip to stop the labour, I went into a coma. That’s when they tested and realised I was diabetic’, says Elaine. ‘Like everyone else that is diagnosed, it was a bit traumatic. It was dificult too because my husband and I had been trying for children for such a long time. We were absolutely delighted. But then we were horrified at the thought that we were going to lose him.’

Post-diagnosis, Elaine says she went through a ‘honeymoon period’, revelling in the happiness of the newborn baby that she and her husband had feared they would never have, but it didn’t last: ‘Everything was fine until they changed to human insulin. Previously it was bovine or porcine and I was fine with that. The human insulin seemed to do me in. I seemed to lose control with the change. I became a brittle diabetic, where I would have a lot of hypos. My body lost the ability to give me the warning signals, so I could be just talking, then I’d have a hypo. Things became dificult—if I was five minutes late, there would be phone calls checking up on me and all of that. I felt like I had lost my independence’.

When the opportunity came up, Elaine was approved as a good candidate for the transplant treatment. She remembers being at work when she received the call telling her the doctors had a pancreas that was a match: ‘They told me they would harvest the cells overnight, so I needed to be at the hospital the next morning. There were so many tests to do, it took all day and it was well after midnight before they came to get me. The nurse must have seen the fear in my eyes and asked if I still wanted to go through with it. I said, “It can’t kill me can it?” They all said “No”, so I said, “Well, we’ve gone this far ...”’

Elaine’s experience with the transplant initially involved being unwell for several months. ‘I was going in for blood tests every day. I was in the hospital so often it felt like I was on staff!’ she says. As Len Harrison points out, ‘We are not made to accept transplants’. Tom Kay agrees, noting the need for anti-rejection drugs, before he adds, ‘The way islet transplantation is currently practised in Australia, it could never have an impact on everyone. There are around 120 000 people in this country with type 1 and there are not enough donated organs’.

Elaine says the day the transplant team needed her to go to a press conference was the day she met Sue in person: ‘I was walking down the corridor and she just looked at me and said, “You must be Elaine”. And then she gave me a big, big hug and told me how happy she was and how good it was to see me. She said the scientists and everyone involved weren’t used to seeing the results, the person behind what everyone was working to achieve’. Her gratitude is obvious when she says, ‘I don’t believe I would have had an islet transplant without Sue’s efforts, her money and her pushing’, although she also admits, ‘I’m not sure I would choose to be the first if I had the chance again. But it’s what we all wanted—to be not dealing with the uncertainty of every day’.

Despite the ups and downs, Elaine remembers her four years of being insulin-free with great fondness. Indeed, needing to go back onto insulin was, she says, ‘My saddest day. I felt like I’d failed. We all get two transplants, and when my islets went down, they initially offered me a third, but then they said no because I’d had issues with the first one’. But while another transplant is not in the offing for Elaine, she does have the latest technology for managing her insulin dependence.

A black device known as a CGM (continuous glucose monitor), which is roughly the size of a mobile phone, clips onto Elaine’s waistband and keeps her blood sugar levels consistent. It represents a significant development in the treatment and management of diabetes, offering the closest thing to a normal life—although with a price tag of many thousands of dollars, the CGM is not an option for everyone. The device has a pump that delivers insulin under the skin in two ways. The first is where small amounts of insulin are delivered continuously, replacing the need for long-acting insulin. The second is where insulin is delivered on demand to account for the carbohydrates in meals or to correct high blood sugar levels. The CGM is worn 24 hours a day but can be detached for up to two hours while swimming, having a shower or playing a contact sport.

Elaine remains delighted by the freedom provided by her monitor/ pump. She also feels heartened by the continual advances in diabetes research, convinced that there will one day be a cure. ‘Seeing a little girl on the television during the Royal Children’s Hospital Appeal, she was so positive when the presenter asked what was wrong with her’, Elaine recalls. ‘She said, “I have diabetes!” I’ll never forget that smiling little face.’ Elaine says that even if it hasn’t been worth it for her, it will be worth it for the little ones: ‘Even if not in my lifetime, there will be a cure’.